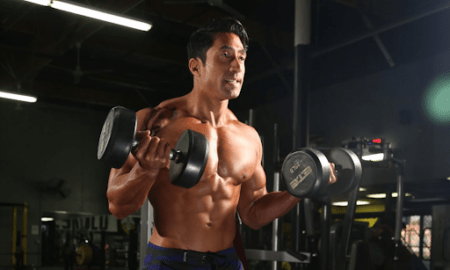

Q: Are there really “upper pecs” and “lower pecs,” or are the pecs two single slabs of muscle?

A: Although the pecs have the same functions in everyone, their outlines vary to some degree among individuals. Check out chest shots of lean bodybuilders, and you’ll see variations in pec shape.

Most people’s pecs have a larger gap between them at the very bottom than higher up. Occasionally, though, you’ll see someone whose pecs don’t have that bottom gap and seem to almost merge into each other right at the bottom line. Steve Reeves, a bodybuilding superstar from the ’40s and ’50s who became a film star, was a famous example of that unusual pec shape.

It’s common to have a hollow in the pecs immediately under the bottom of the clavicles, or collarbones, no matter how well-developed the pecs are, but the hollow is more pronounced in some bodybuilders than others.

Pec shape variations are genetically determined and can’t be changed through training, but the size of the pecs can. It’s the same with other muscles.

For example, some people have highly peaked biceps, whereas others have much flatter biceps—and some have almost totally flat biceps even when they’re fully contracted. For example, no matter how he trained, Sergio Oliva couldn’t build biceps peaks like Arnold’s. The shape of his biceps was genetically determined.

Anatomically, the pecs are the large slabs of muscle on the upper chest, and they connect the chest and collarbone to the humerus, or upper-arm bone. The pectoralis major, the muscle’s formal name, adducts, flexes and medially rotates the humerus. If you move your arm across your chest, pull it down and rotate it inwardly, all against resistance, you’ll feel your pec contract. The pecs are a prime mover of the humerus, along with the delts and lats.

The pectoralis major is a single muscle, but it has a clavicular head, which is the upper area, and a lower area. That’s where the idea of the “upper” and “lower” pecs comes from. Incline-bench presses may place more stress on the clavicular head—the upper pec—than do flat-bench presses.

The pectoralis minor is the muscle beneath the pec major, connecting some ribs to the shoulder blade. The pecs minor aren’t visible, and they have nothing to do with the upper portion of the pecs. They protracts the shoulder blades, as occurs when you reach for something, and elevate the ribs.

Q: At what angle should I set the bench when I do incline dumbbell presses?

A: It depends whether your primary aim is to work your shoulders or your pecs. All angles of the incline dumbbell (or barbell) press work your shoulders and your pecs, but the balance between the areas changes with the angle of the bench. If your focus is on your shoulders, set the bench at a higher angle—about 75 degrees from the horizontal. If your focus is on your pecs, set the bench at about 30 degrees from the horizontal.

Regardless of the angle, make sure that the bench is sturdy and stable, and that the pin or other device that fixes the angle is secure. And be sure to have at least one alert, strong spotter standing by in case you get stuck on a rep. Always be safety conscious.

—Stuart McRobert

www.Hardgainer.com

You must be logged in to post a comment Login