Expert advice to your questions about training, nutrition, recovery, and living the fitness lifestyle.

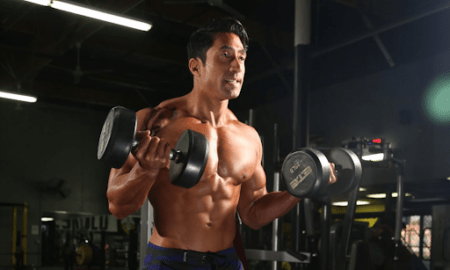

Nathan: I’ve been lifting for 10 years, the last three to four hardcore in terms of really pushing the weights, volume, and frequency. I know my way around a gym basically. Despite that, I’ve never been able to create a strong mind-muscle connection with my chest. Any advice?

Alexander Juan Antonio Cortes: I understand your struggle. This is a common problem for many serious lifters. But there is hope! The following are the principles of muscular innervation, also called the mind-muscle connection.

- Visualize the target muscle as the initiator, performer, and finisher of the exercise. This requires internal mental focus. To achieve eventual unconscious competence with the target muscle, you must start with active awareness first.

- Actively grip the weight. Don’t passively hold on to the barbell or handle. Squeeze it and maintain that pressure throughout the entire movement. Your hands are highly innervative, and your grip connects with all of the major muscles of the torso.

- Remove momentum, and slow down the tempo as necessary in order to establish contractile feel during the exercise. My preferred method is a smooth concentric (quick, but not jerky), a peak contraction at the top of the rep, and then a controlled eccentric. Make this as slow as necessary.

- Lighten your load. Remove your ego from the lifting. If you can’t feel 50-pound dumbbells, 70 pounds won’t make your mind-muscle connection any stronger.

Etan: I’m 43 years old, 6’5, and 260 pounds. I’ve been training my whole life and know I have a decent base of muscle, but I’ve never been lean. I’ve always wanted to look ridiculously cut up. Is it still possible at my age to get ripped?

AJAC: Yes, it’s possible, but unfortunately, I can’t say its probable. This comes down to a question of the commitment you are willing to make. The older you get, the harder dieting tends to be. And if you’ve never been truly lean, this will be your first time following a strict dietary regimen and being consistent. Realistically, it may take up to six months to get truly “ripped,” assuming you’re starting with a body fat percentage in the mid-teens. Four to six months is a realistic time frame. Understand that this “ripped” state will be entirely temporary, and that the very low calories required to get ripped will not be sustainable. You will need to “reverse diet” your way back to a more normal bodyweight and body composition.

A better approach would be to take two to thee years to slowly recomp yourself. This would be accomplished through short-term diets and long-term periods of cruising while maintaining a lower bodyweight. Over time you could steadily get leaner. This approach is the most sustainable, although it will likely mandate seeking out some expert help.

Nabeel: I’ve heard about fructose being something you should avoid in your diet. It can cause fatty liver disease, easily converts to fat, and overall is bad for your health. Is this true?

AJAC: In a word, no. The reason the fitness world has demonized fructose can be traced back to around 2004. A research paper was published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. It speculated that America’s increase in obesity since the 1970s was tied to increased consumption of fructose, specifically high fructose corn syrup (HFCS). This paper did not “blame” fructose per se, but said more research was needed. The fact that the increased high fructose corn syrup equaled increased calorie consumption was largely ignored.

The fitness industry took the paper out of context though, and HFCS become the new demon carbohydrate to avoid eating.

Fructose, when consumed as part of an isocaloric/maintenance diet, it does nothing that is “bad” in the body. The ill health effects are only seen when it is overconsumed on a hypercaloric diet for long periods of time. In layman’s terms, if you overeat a ton of sugar and get fat from it, it will probably have a negative effect on your health. So no, fructose is not unhealthy so long as it is consumed reasonably.

Ricky: Is there a certain amount of time that someone should spend doing mobility work each week? I’m concerned my flexibility has decreased, and I’m not sure what the best way to address it is.

AJAC: Are you training with a full range of motion? If not, I’d suggest starting there first. While flexibility can certainly be worth addressing individually, many tightness issues are the result of someone’s training, not because of a lack of stretching. If training is not the issue, then the simplest and most direct way to begin improving flexibility is to static stretch. Ten minutes daily of stretching the hamstrings, groin, quadriceps, spine, and shoulders will make an immediate impact on your active range of motion.

Sasha: I know these kinds of questions are annoying, but is the bare minimum of exercises someone could do and still look muscular?

AJAC: Actually this question is entirely reasonable. Determining a minimum number of exercises is a better premise to start from versus asking what the “best” exercises are. Relative to the potential movement of the human body, we can do two things: We project force outward, and we can pull force inward. That equates to pressing and pulling. From there, we can divide the body into quadrants of movement: vertical (up and down) and horizontal (forward and back). A way to think about this would be north and south, then east and west. Applying this model to the upper body, we can determine four basic movements:

- Upper-body vertical movement: Pull-ups and dips

- Upper-body horizontal movement: Push-ups and inverted rows

- Lower-body vertical movement: Squats and step-ups

- Lower-body horizontal movement: Deadlifts and sprints

Now, some people would argue with the above, but overall, building a program around the following movements, and nothing else, you’d be reasonably

You must be logged in to post a comment Login