I know it’s difficult to accept the notion that Overhead Presses – an exercise that has been around for decades, and has been considered one of the most fundamental exercises in weight training since its inception – might actually not be so good after all. That concept might seem outrageous to you. You’re probably thinking, “how can that be?… it’s in all the fitness books; we see it done in all the gyms; it’s been done by thousands of successful competitive bodybuilders… it’s ludicrous to think that it’s not a good exercise!” But allow me to explain some basic facts, and then you can decide for yourself.

Problem # 1: Not the Right Movement

Let’s start with the assumption that your intention is to work your shoulder muscles (i.e. the deltoids – specifically the center section, known as the “lateral deltoid”). If you were to look up the function of the lateral deltoid in an anatomy book you would discover that the function of the lateral deltoid is “lateral abduction”. This is a term which means “to move the arm laterally, out to the side, away from the body”. That’s what the lateral deltoid muscle does – exclusively. In other words, when we perform a “straight arm side raise”, with a dumbbell or a cable, we are duplicating the exact function of that muscle – and that is the way it should be. But when we do an overhead press, we are not performing a “lateral abduction”. We are performing a movement that has a vague similarity to lateral abduction, but is different.

Similarly, if your goal is to work the front deltoid, you need only examine the primary function of that muscle. The primary movement performed by the anterior deltoid is one that moves the arm from a position alongside your body, toward the front – not toward the side. There are other exercises that specifically DO what the front deltoid does, that work that muscle much better, with no risk of joint injury. For a better understanding, read – “Front Deltoid Options”, found here: http://www.ironmanmagazine.com/blogs/dougbrignole/?p=159

In any case, the point is that the Overhead Press is the wrong movement for both the side deltoid, AND the front deltoid.

Let’s compare that with another muscle – the biceps. If we were to look up the function of the biceps (of the arm), we would find a description which clearly states its function as (primarily) “elbow flexion” (… to a lesser degree, it also moves the upper arm forward, because it also crosses the shoulder the joint – technically speaking). This is the term for “bending the elbow”. And when we do exercises for our biceps, we perform movements that are exactly (and exclusively) like the description of that function – curls – which is “elbow bending”. We might do curls with dumbbells, or with a cable, or with a machine. But in all cases, we perform an elbow flexion. And the reason we do that is because that is what the biceps does. It would be impractical and illogical to do something other than elbow flexion, and still expect maximum stimulation of the biceps.

We could make similar comparisons for every other body part – the quadriceps extend the knee, and when we do leg extensions or squats, we extend the knee (note: squats involve knee extension, plus hip extension). The triceps extend the elbow, and when we do triceps pushdowns, or lying dumbbell triceps extensions, we perform “elbow extensions” – duplicating the function of that muscle. But when we do overhead presses, we are not duplicating the function of the lateral deltoid. We are doing something different, yet somehow have accepted this aberration as a “good deltoid exercise” – even though it does not follow the same rule as every other exercise, for every other muscle in our body. The rule is: “An exercise must perform the function of a given muscle, in order for that muscle to receive maximum benefit”.

Problem # 2: Excessive External Twisting of the Joint

A number of years ago, the American College of Sports Medicine issued a “Position Paper”, describing the “Safe” and “ Unsafe” range of shoulder rotation. In order to understand this concept, hold your arm straight out to the side, parallel to the ground. Now bend your elbow so that it forms a 90 degree bend. Now – keeping your elbow at that exact height, lower your hand so that your forearm begins sloping downward. This downward rotation is called “internal rotation of the humerus”. Now – rotate your arm the other direction, so that your forearm is sloping upwards. This action is called “external rotation of the humerus”. The rotation is actually occurring within the shoulder joint. There is – in fact – a limited amount of internal and external rotation that is safe. This is obvious. You can easily discover this for yourself, simply by rotating your arm downward until you begin to feel discomfort (i.e. pain) in the shoulder, and then rotating it upward until you begin to feel discomfort in the shoulder.

What this little experiment – and The American College of Sports Medicine – establishes, is that the safe range of shoulder rotation is in the middle. Generally – and this differs a little from person to person depending on their degree of shoulder flexibility – the safe range is from the level position, downward about 45 degrees and upward about 70 degrees. Rotating the arm farther up or down is considered “extreme” and unsafe, and officially referred to as “excessive internal rotation” and “excessive external rotation” – of the humerus. So, in order to perform an overhead press, one must enter the unsafe zone of external rotation (90 degrees), and then – at the point where the shoulder is mechanically strained to the upper-most limit – add resistance! It’s almost like trying to do curls behind your back.

Problem # 3: Rotator Cuff Strain

Let’s examine what happens if – and when – a person is unable to rotate their arm to a position where their forearm is perpendicular (straight up), due to limited flexibility in their shoulder, which is fairly common. Hold your right arm in the starting position of an overhead press, but with your forearm at a slight forward slant. Imagine that you are pushing a dumbbell upwards, toward the ceiling. Now consider this: the slight forward slant of your forearm is causing the weight to pull your forearm (actually, your hand, with the weight in it) forward, and in order to keep the weight from falling farther forward, you must perform a sort of “reverse arm-wrestling” movement, while still pushing upward. In other words, you are using your external rotator cuff, to prevent the weight from falling forward. The problem with this is that the weight is too heavy for that type of movement. The external rotator cuff is small, compared to the deltoid. You have selected a weight that is appropriate for your deltoid, but now you are using your (much smaller and weaker) rotator cuff to keep this weight from falling forward. This could easily cause “rotator cuff strain”, and might well result in shoulder pain. It could actually cause your rotator cuff to tear, when done repeatedly, and/or with a heavy weight.

A similar problem occurs when one is performing a “Behind the Neck” barbell press. In order to keep from hitting yourself on the head with the bar, you must keep the bar behind your head. This forces you to angle your forearm slightly backward, which rotates your humerus externally even farther than before. Now you are combining a more severe external twisting of the shoulder, with the fact that the weight wants to fall backward, and you are forced to use your internal rotator cuff to prevent it from going farther back. In essence, you are arm-wrestling the bar, at the same time that you are pressing it upward. This makes no sense. You would never think to strain an unrelated body part while doing curls for your biceps, or leg extensions for your quadriceps. Why is it acceptable to strain your rotator cuff, simply to work your side deltoids – especially considering that the sole function of the side (lateral) deltoid is “lateral abduction” – not joint rotation? Lateral abduction (i.e. working the side deltoid) does not “require” that you simultaneously twist the shoulder joint, and overload the rotator cuff.

Problem # 4: Improper Range of Motion and Impingement

Every muscle has a point of full extension, and a point of full contraction. For example, your biceps are at full extension when your arms are straight, and they’re fully contracted when your elbows are completely bent. The rule is: “For maximum benefit, an exercise must mimic the natural range of motion of the working muscle”. A curl, therefore, goes from arm straight, to arm bent – from the point where the muscle is extended, to the point where the muscle is contracted. The same is true with every other muscle, in every other exercise. Consider the Leg Extension (for the quads), the Dumbbell Row (for the lats), the Calf Raise (for the calves) – all begin at full extension (where the muscle is elongated), and finish at the point where the muscle contracts (i.e. flexes).

The range of motion of the side deltoid begins at the point where the arm is straight alongside your body, and it concludes its range of motion (muscle fully contracted) at the point where your upper arm is perpendicular to your body (i.e. straight out to the side). However, as you can easily see, the overhead press does not begin at the point where your upper arm is straight alongside your body, and it ends at a point much farther up than “perpendicular to the body”. In other words, it loses a significant percentage of the early range of motion (an important part of the range of motion), and it goes far past the point of normal contraction, to a point known as shoulder “impingement”.

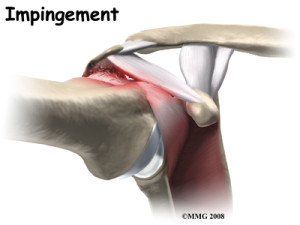

Impingement occurs when the upper arm bone approaches the side of your head, and pushes against the upper edge of the shoulder blade (also known as the “acromion process”), causing irritation of the supraspinatus tendon. This typically causes inflammation, which is commonly known as “impingement syndrome”. In severe cases, the tendon could actually tear. In the illustration below, you can clearly see the supraspinatus tendon coming through the space between the humerus and the underside of the acromion process, as it attached to the head of the humerus. You can also clearly see how bringing the humerus higher than perpendicular to the torso causes this tendon to become pinched. Google the term “impingement syndrome” (and then “images”) and you’ll see dozens of images from different angles showing the supraspinatus tendon being pinched when the arms are put into an overhead press position. Doing this occasionally will not cause a problem. However, doing this repeatedly, with heavy resistance, is inviting an injury.

Problem # 5: Improper Alignment of the Muscle

Another rule that exists in biomechanics is that: “a muscle must be positioned opposite resistance, in order for that muscle to benefit from the resistance”. That might sound complicated, but it’s really very simple. To demonstrate it, stand in front of a mirror, and imagine that you are actually lying on your back, on a bench, looking up at a mirror that is on the ceiling. Now, hold a pair of 10 pound dumbbells in the same position you would be in, if you were about to do a “flat dumbbell chest press”. Now – push those dumbbells toward the mirror – still imagining that you are lying flat on a bench, pushing those dumbbells toward the ceiling. Do about 10 repetitions. Now ask yourself, “do I feel fatigue in my pectorals, or do I feel fatigue in my shoulders?” The answer, you will find, is that you feel fatigue in your shoulders, and NOT in your pectorals – even though you are performing a movement that is typical of a “chest press”.

The reason for this is because – in this little experiment – while you are in the standing position, the resistance is not coming from behind you, opposite the pectoral muscles. If you were really lying flat on your back (looking up at the ceiling), gravity (i.e. resistance) would be coming from behind you, and your chest muscles would be positioned on the opposite side of the resistance. As such, your chest muscles would be perfectly aligned opposite resistance, and would therefore receive the benefit of the resistance. But, as you discovered in this little experiment, when the resistance is coming from a direction OTHER than opposite the pectorals, the pecs do not get the benefit of the resistance.

This is what happens – to a large degree – during an overhead press. By rotating the arm externally, to the point where the forearm is perpendicular to the ground, you automatically rotate your lateral deltoid toward the rear, and away from the position that is best suited to oppose the downward resistance (gravity). Instead, you rotate your frontal deltoid up into a position that is more in opposition to gravity. In fact, if you were to look to the side, at your deltoid, while performing an overhead press movement (even without using weight), you will observe (especially if you are lean enough to see the division between your front and side deltoids), that the “position opposite the downward resistance” (i.e. on the top side of the shoulder) is occupied about 70% by the frontal deltoid, and about 30% by the side deltoid. This means that 70% of the resistance is benefiting the frontal deltoid, and only 30% of the resistance is benefiting the side deltoid. And even this comes at the expense of joint strain.

Why We’ve Done Them For So Long

Why would anyone choose an exercise that has less benefit and more risk, over exercises that have more benefit and less risk? There are several reasons, but primarily – tradition. When “weight lifting” (the act of lifting a heavy object, for the purpose of developing physical strength) first originated, there was no knowledge of “biomechanics”, and lifting objects UPWARD was the standard. Since then, it’s been grandfathered in, and accepted as one of the “basic” weight lifting movements. Second reason – illusion and ego. Lifting a heavy weight – even if it’s due in large part to the advantage of leverage and assisting muscles – creates the impression that one is strong, and lays the groundwork for competitiveness.

We’ve also had blind belief in those who came before. We look at someone like Arnold Schwarzenegger, and assume that if he did them, they must be good. Many successful bodybuilding champions have used Overhead Presses, and they look impressive, so we make the mistaken assumption that all of the exercises they’ve done in the gym, have contributed equally to this result. Many football players – college as well as professional – have traditionally used them in developing power for their game, and we mistakenly assume that what’s good for a young, large-boned, power athlete is also good for someone with the goal of fitness or bodybuilding.

But none of these reasons are sound, from a scientific or factual perspective. Chances are that you’ve done them despite feeling shoulder pain, thinking that the pain was not coming from the exercise, but instead was coming from your own unique weakness. You’ve probably ignored obvious signs of strain, simply because you thought “the exercise can’t possibly be bad…it’s been around forever”. And perhaps you even thought that shoulder strain is the price that must be paid in order to gain the muscular shoulder development you want. These are all errors in judgment, based on years of misinformation.

What We Should Do Instead

Since the Lateral Deltoid does only one thing – lateral abduction (i.e. a side raise movement) – the very best exercises for the Lateral Deltoids, are those which perform precisely that movement. Let’s again compare this with working your biceps. During a workout, you might do two or three exercises for your biceps – a preacher curl, a cable curl, a machine curl, etc. – but it’s always a curl…. because that is what your biceps does. However, by changing from one “curling” exercise to another, you are changing the direction of the resistance, and therefore the “resistance curve” – which is the sequence of changes in resistance that a muscle encounters through the range of motion of each exercise (each exercise has a different resistance curve). These “changes in resistance” occur as a result of the changes in lever positions (i.e. a lever encountering horizontal force versus a lever encountering parallel force). In some exercises, the resistance is greater in the beginning (like in the preacher curl), while in others the resistance is greater toward the end of the range of motion (like in concentration curls). These types of changes are good. But the movement itself needs to stay consistent with the muscle’s function.

Likewise, when selecting your side deltoid exercises, the best thing is to choose a variety of types of “side lateral movements”. For example, you might first do a seated (vertical) side dumbbell raise, following by a horizontal side dumbbell raise (while lying sideways on the floor), followed by a cable side lateral raise. Here, you have three distinctly different resistance curves, while still maintaining a strain-free mechanical movement, and getting 100% of the benefit. In the first exercise (#1), you’ll notice the resistance is greatest when your arm is at the end of the range of motion (when your arm is perpendicular to your body). In the second exercise (#2), you’ll notice the resistance is greatest at the beginning of the range of motion. And when doing the cable side raise (#3), you’ll notice the resistance is greatest somewhere in the middle of the range of motion.

Another option is dumbbell side raises while lying sideways on an incline bench, at a 45 degree angle, one arm at a time. You can also vary the degree of incline, anywhere from 45 degrees down to 15 degrees, assuming your bench offers those options (each change in the degree of incline offers a different resistance curve). And yet one more option is a side lateral raise on a machine, which maintains more of a constant resistance throughout the entire range of motion (due to the machine’s “cam”). Every change of angle, changes the stimulation that the muscle experiences, and offers a new “feeling”.

Side Raises Are King: The Benefit of a Longer Lever

Rather than shunning straight-arm-side-raises because you aren’t able to use a very heavy weight, you should embrace and appreciate the advantage of having a nice, long lever (your extended arm), with which you can magnify the weight you are using.

For example, if you were to do a straight-arm-side-raise, with a 15 pound dumbbell, the deltoid would actually be lifting much more than 15 pounds because the length of your lever (i.e. your arm, which is approximately 20 – 24 inches long) is magnifying the weight – by a factor of approximately 15 (multiply the weight you’re using, by 15). Thus, your deltoid would be lifting as much as 225 pounds, without strain to the joint! That’s a significant work-load! A straight arm side raise with even a 5 pound dumbbell would deliver approximately 75 pounds of resistance to the deltoid. Don’t believe me? Try lifting a sledgehammer – with a 15 pound hammer head – by the end of the handle, with one hand. That’s precisely what your deltoid would be lifting, every time you do a straight-arm-side-raise.

Putting It All in Perspective

Whether your goal is to improve your physique or to improve your health, the overhead press is a poor choice. It’s true that many bodybuilders have done them, and it would appear that they have benefited from them. But in reality, it’s very likely that they benefited less from overhead presses, and more from side raises, and – if they were lucky – they might have avoided serious injury. Many have not been so lucky. It would be a mistake to assume that all exercises have the same amount of benefit, and the same amount of risk. Each exercise has its own benefit / risk ratio.

Also, don’t be fooled into believing that overhead presses are better than side raises, simply because you can use a heavier weight while doing them. The reason you can use a heavier weight is because you are using a bent arm, instead of a straight arm (i.e. a bent arm reduces resistance – resulting in better leverage, while a straight arm magnifies resistance). Also, the triceps contributes significantly to the movement, but creates the illusion that the deltoid is lifting more weight. In truth, the deltoid is not working any harder than it would during a side lateral raise.

A good compound exercise (i.e., one that involves two or more joints and muscle groups simultaneously) is one which combines two or more NATURAL movements – like a squat, or curling while simultaneously stepping up and down on a stool. An overhead press combines several movements, but only the triceps action is “natural”. Don’t fall into the trap of thinking the overhead press is a “good compound exercise” because it saves time by working several muscle groups at one time. The fact is, while you are involving several muscle groups in doing an overhead press, you are producing joint strain, and gaining only a compromised benefit to the muscles involved. Saving time is good, as long as it doesn’t result in an increased risk of injury, and a lesser benefit than other perfectly good exercises.

It makes good sense to eliminate overhead presses, if your goal is health, fitness or bodybuilding. Power lifters and certain athletes like shot putters, would benefit from overhead presses – strictly from a sports performance standpoint, even though they would still be exposed to the risk of injury.

Old habits are difficult to change, but try replacing overhead presses with a variety of side raises. If your goal is to make your deltoids bigger, use a substantial weight, with good form, for 6 to 10 reps per set. I’m confident you’ll see better results. Plus, you’ll avoid a shoulder injury, and your aching shoulder joints will suddenly begin feeling better.

21 Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment Login