Q: I’m starting to see pinitol in a number of products. Tell me how it works.

A: Pinitol, more specifically D-pinitol, is a methoxy analogue of another sugar called D-chiroinositol. A methoxy analogue means that one molecule is very similar to another except for a small substitution on one of the side chains.

D-chiroinositol is a form of the sugar inositol that can be detected in urine. Research has found that D-chiroinositol levels are reduced in insulin-resistant monkeys and humans, including type II diabetics. Giving the monkeys D-chiroinositol improved glucose utilization, leading to lower blood sugar. D-pinitol, an orally available form having similar effects to those of D-chiroinositol, has been receiving scientific attention in the hopes that it, too, can help with blood sugar control.

How does it work? Studies are still being conducted to determine just that. The picture is a little clearer since the publication of a study in the August 2000 British Journal of Pharmacology (Bates, et al. 130:1944-1948). The study demonstrated that D-pinitol decreased blood sugar in rats made diabetic after exposure to a chemical that fried the pancreas. The rats couldn’t make sufficient insulin, which caused their blood sugar levels to rise. Providing D-pinitol reduced blood sugar levels to near normal, but it didn’t affect the insulin levels.

On further investigation, it appears that D-pinitol requires an intact insulin receptor ‘system’ in the membranes of cells and that insulin may be a more potent signal, easily overwhelming the effect of D-pinitol in the rats. D-pinitol seems to offer benefits in intact insulin receptor systems in subjects who have inappropriately low insulin levels in a state of hyperglycemia, or high blood sugar.

What’s more, in a test using muscle cells grown in a petri dish, both insulin and D-pinitol were shown to increase glucose uptake into the muscle cell; however, when the two were added together, D-pinitol didn’t have that effect. It was noted that D-pinitol was capable of increasing glucose uptake into the cell to the same level as insulin, in the absence of insulin.

Does that make it an insulin substitute? We can’t say that yet. The last part of the study looked at how D-pinitol works relative to a specific postreceptor event involving the PI3K enzyme. Here’s what the researchers found.

Insulin hits the receptor on the outside of the cell membrane. That causes the receptor to release something to the inside of the cell called IRS-1. IRS-1 may be D-chiroinositol, for which D-pinitol can be substituted. IRS-1 and D-pinitol appear to activate the PI3K. That leads to the cascade of events that is insulin’s ultimate effect.

How do the scientists know that both insulin and D-pinitol use this enzyme? They blocked the enzyme with a chemical that prevented it from becoming active. When the PI3K inhibitor was present, neither insulin nor D-pinitol could induce the uptake of glucose into the isolated muscle cells. That’s significant because if both insulin and D-pinitol require the same enzyme system to work, then having them both trying to activate the same enzyme is competitive. Competition does not lead to greater results. Cooperation does (just as they told us on ‘Sesame Street’).

Here’s what we might infer from the results of the study: D-pinitol improves the blood sugar in diabetic rats, which are unable to produce sufficient insulin; D-pinitol does not interfere with insulin; D-pinitol is as effective as insulin in driving sugar into isolated muscle cells.

We’re left to wonder if D-pinitol would increase muscle cell uptake of glucose if less-than-maximal insulin were present, as may be seen in ketogenic, or low-carb, diets. D-pinitol may belong in products that have a limited carbohydrate content, less than 30 to 35 grams of sugar, or should be taken with low-glycemic meals. If the results of rat studies are applicable to humans, it probably won’t be of great benefit in terms of glucose utilization, in high-glycemic, high-carb products. On the other hand, it would be worth investigating D-pinitol’s effect on amino acid and creatine uptake.

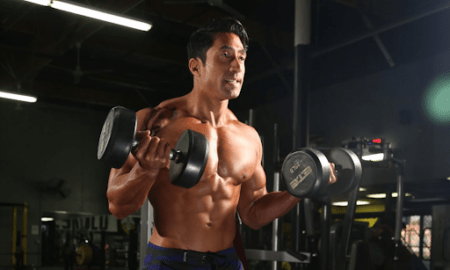

Q: I’ve seen some photos of you doing curls, and you have a split in your biceps. What exercises work a split like that?

A: Exercising discipline in your diet is the only way you’ll ever see a split in your biceps. Muscle definition doesn’t occur if your bodyfat is higher than 8 to 10 percent. The biceps brachii is a muscle group with two separate muscle heads. The two heads of the biceps, which end in a commonly joined tendon, originate from two different points. The short head of the biceps connects to a part of your scapula and the long head connects to the top of the upper-arm bone. Let’s be real: There’s only so much you can do with a muscle that acts on a joint that’s a fixed hinge.

Do not neglect to do everything possible with the muscle, however. The biceps is involved in two different movements. Flexion at the elbow joint (bending the arm) and supination at the wrist (turning the palm up). Most people focus on the flexion portion of the movement. Using fixed-position bars and handles will restrict any rotation of the forearm (the supination of the wrist). Don’t get me wrong, I love doing straight-bar curls. I think it’s one of the best mass-building exercises for the biceps. But to get any development that will emphasize the split in your biceps, you need to include the rotation component.

I keep putting, ‘Make a workout video,’ on my list of things to do. One of these days. Here’s what you should consider when you work your biceps: Your body is designed to move in arcs, not in straight lines. When your arms are hanging naturally, the palm faces the thigh and there’s a slight bend at the elbow. Now, reach up and scratch the top of the shoulder of that arm without moving your elbow. You’ll notice that the little finger is curled toward the top of the shoulder. Really flex the muscle in that position and you should feel the biceps almost cramp. Keep that feeling in mind, because you’re going to try to achieve that at the top of each rep. Slowly return your arm to its natural hanging position. Notice how the palm turns so that it’s open and upward midway down and remains up until the last couple of inches of the movement. Practice moving your hand up from the hanging position to the top of your shoulder, keeping your elbow in place.

Then repeat the motion, flexing the biceps as you go through it. Once you’re sure that you can do the biceps curl in a controlled and disciplined manner, you can pick up a dumbbell. Start light, so you’re not required to move your elbow or swing to get started. Focus on getting your palm turned up quickly, as that’s the key to focusing on the biceps.

That’s the basic dumbbell curl. Of course, there are variations, and I haven’t talked about the breathing routine during the motion. I guess it’s one more indication that I need to get the workout video going. I tell you what. If I can find 500 people who want the video, I’ll do it. Otherwise, I’ll be wallpapering my office with unsold, dust-gathering, soon-to-be-released-in-garage-sales-everywhere tapes. Get in touch with me, and I’ll keep track. If there’s enough interest, I’ll do the video. You can contact me via e-mail at [email protected].

Editor’s note: Daniel Gwartney, M.D., is a clinical pathologist and a graduate of the University of Nebraska College of Medicine. He’s been bodybuilding for more than 18 years. The material presented in this column is for general-information purposes only and is not to be construed as medical advice or an individual recommendation. Consult with your physician or health care provider before embarking on any fitness, training, diet or supplementation program. The author and IRONMAN assume no liability for the information contained in this column. IM

You must be logged in to post a comment Login